Growing up in a family with few economic resources, Elijah Amoo Addo knew what it meant to go hungry. But through determination, access to public education, and a deep passion for food, Addo became one of the most promising young chefs in Accra, Ghana, by his early 20s.

A chance encounter led him down a slightly different career path, though—one that led to the founding of Food For All Africa, one of the first food banks in West Africa, in 2014. That same year, Addo connected with The Global FoodBanking Network for the first time, a relationship that he says has significantly changed the way his food bank operates, for the better. To date, Food For All Africa has served more than 15 million meals and recovered more than 1 million kilograms of food.

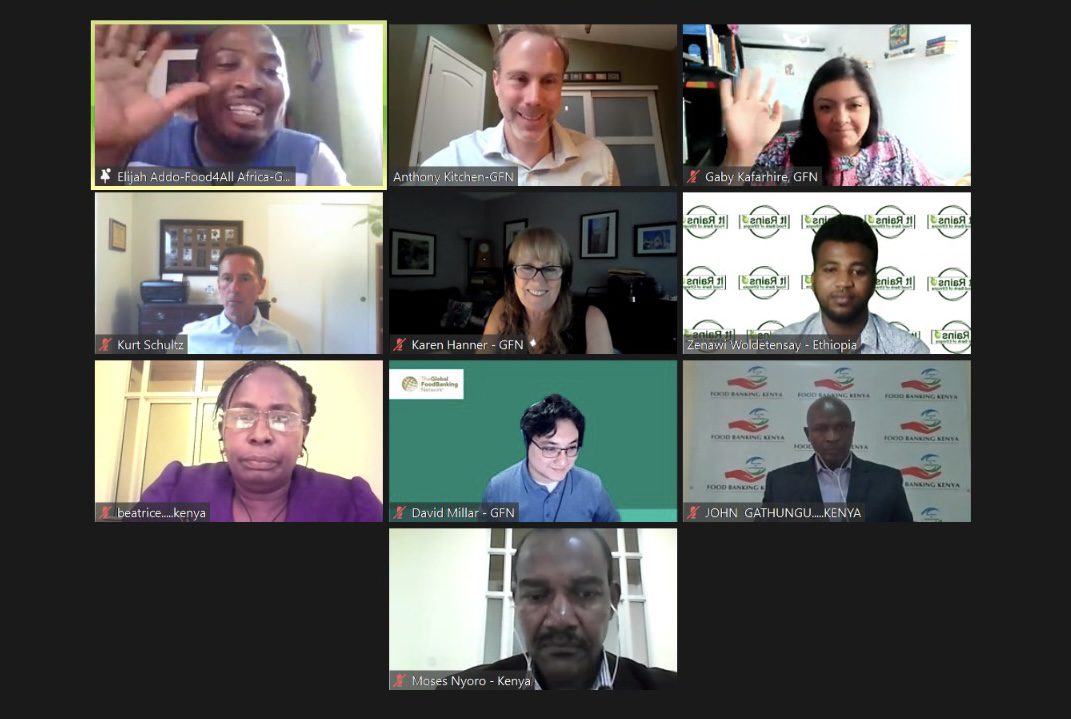

We recently spoke with Addo to learn more about his inspiring story, the early challenges of running a food bank, and how GFN helped Food For All Africa move achieve its goals more quickly.

Chef Elijah Amoo Addo: I lost my parents very early. As a 12-year-old boy, I started seeing the world from a different perspective. Initially, when my parents were around, I saw the world as a place where someone was always covering you. But that changed quickly, and it also changed our economic situation when [my three siblings and I] were left in the care of my grandma, who was a retiree. So I had to go through waking up and not having food on the table. That, and taking care of my sisters and myself, it made me want to be one human who would always want to look out for the welfare of others.

Before my parents passed away, I was closer to my mom and would spend time with her in the kitchen, sitting together, conversing. Because of that experience, I connected easily with cooking after I finished school and built the skills I needed to become a chef.

One day at the hotel restaurant where I used to work, I came into contact with a man struggling with mental illness who was picking leftover foods out of the trash. And then he went out into the street to feed his friends. After seeing him do this over several days, I asked him why he was doing that. His response was, “If I don’t do it, who will?”

It made me see that I couldn’t sit on the fence if I could do something about the hunger situation in our community. It meant there was a break in the food system. That’s why I started Chefs for Change Ghana Foundation, with the sole objective of recovering excess food along the hospitality chain to feed vulnerable people. I mobilized a group of chefs, and it became the norm for us.

As the years went by, I got more interested in food waste and got to study more about how the food supply chain works, especially in my part of the world. But what was shocking for me was that as at that time, I found estimates from FAO in 2011 showing that almost 45% of food goes to waste along the supply chain in Ghana at a time when we have over 40% of children go to bed hungry.

The experience made me see that indeed food waste was not just limited to the hospitality sector but was present in different sectors of the supply chain. And my interest grew more in feeding those who can’t pay than those who can afford the hotels and the restaurants. So in 2015, I said to myself, this is what I want to do for the rest of my life. And I formed Food For All Africa.

Because the organization was built from the hospitality sector, we were mostly recovering food from the hotels and the restaurants. This is cooked food that needs to be handled within a certain temperature. We needed cold chain, a cold van—there has to be a way to package the food so it gets to beneficiaries in a good state. That was the challenging aspect of it.

And I was a young chef who at first had to balance both my job as a chef and then recover food for institutions serving vulnerable people. So what I did was, I spoke to all the charity homes within Accra, the children’s homes, community schools, community libraries, community charities, got their contacts, then spoke with all the different chefs I know.

I used to be secretary of the Chefs Association in Accra, so I had a network of chefs within the hospitality sector. At the end of my shift, they would always send me a WhatsApp or text to say, “I have this, if you can come for it early in the morning, I’m keeping it in the fridge.” That night, I had to do calls to the beneficiary charities and connect them, saying, “Tomorrow, you pick this up from here, you pick that up from there.” Most of the time, we could connect them, but transportation for the charity homes was also challenging. So I thought that, if we could have our own van so we could deliver the food, that would be better than calling.

So we looked at ways and means to get a van, and that was also challenging. But we had a donor who loved the idea and gave us a van. With the van now, we weren’t just picking up food from the hospitality sector for charities. We were able to give food to those who live on the street, homeless, as well. Some restaurants agreed to give whatever leftovers they had from their buffets, and we would take it to different areas within Accra. So Food For All was actually built on picking up cooked food from the hospitality sector to feed homeless and vulnerable communities.

Our partnership with The Global FoodBanking Network has been phenomenal. It’s been phenomenal. It’s been life changing. From even the initial emails with [GFN cofounder] Mr. Chris [Rebstock] in 2014 and online information, we learned quite a lot. And really, it was through that platform that I got to really understand what food banking was and the various opportunities within the food supply chain and how those opportunities are affected by liability laws and tax benefits in the country. That gave us a clear-cut vision on the areas we needed to focus on as a food bank startup and how we could gradually scale to other sectors as we go on.

In 2019, we were fortunate to be invited to participate in the Food Bank Leadership Institute [now called the GFN Global Summit] in London. It was there that our relationship really took off from a technical and funding point of view. The relationship with GFN gave us the opportunity to first and foremost get to understand, in practical terms, what a food bank should be, what structures a food bank should put in place, what operating models a food bank can adapt, and the feasibility studies necessary. From that onset, the relationship with GFN gave us knowledge on how to approach potential donors and partners in this part of the world.

That was a gamechanger for us as a small organization.